Image: Atomwise CEO and co-founder Abraham Heifets

Is price control by stealth the future for the United States?

In the absence of state price negotiations, experts continue to explore other ways to introduce price control under federal drug programmes by stealth.

Dr Judith M. Sills. Credit: Arriello

Dr Eric Caugant. Credit: Arriello

As is customary, as January begins, so do price increases in the United States. Several reports tracking January price hikes are typically issued and pressure on US policymakers to do something about domestic pharmaceutical price increases intensifies. This year is no different.

Price hikes scrutiny replicates trend seen every January

A report from GoodRx earlier this month showed the price of 434 branded drugs increased by 5.2% on average in January. On 13 January, GoodRx updated its price hikes list to include 694 brand-name drugs, with an average price increase in January of 4.8%.

In recent days, US-based non-profit organisation Patients for Affordable Drugs (P4AD) came out with its own price hikes list based on a different methodology. It identified 1,678 unique national drug codes (NDCs) whose wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) increased by more than 1% between 1 and 5 January. Of those, 1,377 NDC had a price increase of $1 or more. The shortlisted 1,377 NDCs correspond to 554 pharmaceutical products (defined as having the same brand name and being sold by the same manufacturer). The organisation found that the average price increase for the 554 products was 6.3%. For 183 of these products, the price increased by $100 or more, while 118 products after the increase have a price of more than $5,000. P4AD further found that 93% of the price increases were for branded drugs. For a quarter of the 554 products, the price increase this January exceeded the 6.8% consumer price inflation recorded for the 12 months to November last year and 93% of price increases were higher than the 2.3% inflation rate that has been forecast for next year.

There is a major caveat to all of these studies – they only track list prices and do not show discounted net prices, which have very different trends compared to what is happening at the WAC levels.

Yet 2022 brings higher price control threats

While price scrutiny may be similar to previous years, there is a sense that now the time may be ripe for the introduction of price controls. The Democrats – who traditionally have been more likely to push for price controls – now hold the presidency, the majority of the House and would, with Vice President Kamala Harris’ deciding vote, have 50% +1 of the votes in the Senate. They are not, however, all in agreement over what shape price control reforms should take. President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better bill, which contains some drug price control measures, was passed by the House of Representatives by 220-213 in November but is yet to be voted on by the Senate. Democratic Senator Joe Manchin pulled his support from the bill last month, effectively ensuring it will not pass in the Senate, but negotiations are still continuing.

The Build Back Better bill contains measures to limit pharmaceutical price increases to the rate of inflation and, unsurprisingly, P4AD has come out in support of the bill. The organisation has sent its price hikes report to more than 400 Congressional offices, as well as members of the patient community, to help create support for the Build Back Better bill. While the measures in the bill fall short of full price control, they can be seen as a first step in the direction of direct government price control for medicines. If the link between inflation and price increases existed today, it would have meant lower price increases for at least a quarter of the 554 drugs if historical inflation is considered and for 93% if the 2023 inflation rate is taken into account.

US is unique in terms of price increases post-launch

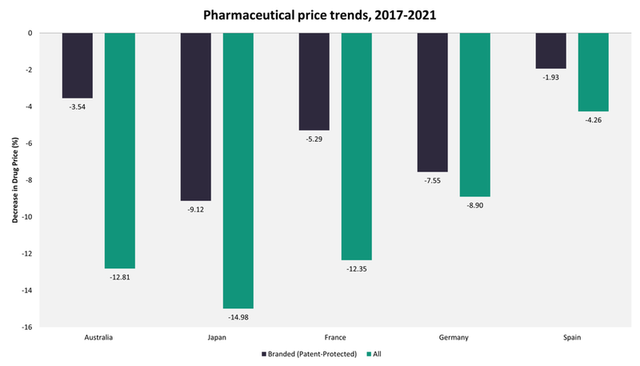

The trend of price increase for pharmaceuticals after launch is relatively unique to the US. Not only are US launch prices generally higher, but the gap between US prices and those in other countries with a comparable per capita gross domestic product (GDP) tend to increase over time as prices in the US increase, while in other countries, they remain stable or decline over time. Data from the GlobalData POLI database indicate that in Japan, pharmaceutical prices declined by 9.12% for branded medicines and by 14.98% for all marketed medicines over the last five years, while in Germany, they fell by 5.29% and by 12.35% respectively.

Even if direct price control is not approved, CMS has other measures up its sleeve

Aside from the free pricing of medicines, the main reason for price disparities between the US and other countries with similar GDP per capita is that the government is not allowed to engage in direct price negotiation with the pharmaceutical companies. Various methods for implementing pharmaceutical price control have been considered in the US, including the introduction of International Reference Pricing (IRP).

Even if the Build Back Better bill is approved, it would not amount to full price control. But nevertheless, it would be an important first step in price control to the extent that it will put a cap on price increases after launch.

While implementation of government price negotiations remains some way off, there may be ways of introducing price control under federal drugs programmes by stealth.

In the absence of a national health technology assessment (HTA) agency, whose decisions are binding, the CMS has recently resorted to playing the role of an HTA agency by limiting Medicare reimbursement of Biogen’s expensive Alzheimer’s drug, Aduhelm (aducanumab), to Coverage with Evidence Development (CED) only. Decisions to limit reimbursement to CED are typically undertaken by HTA agencies, such as the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). The CMS decisions are so far in draft form and may yet change to allow broader reimbursement access. In other countries, the threat of limiting reimbursement in a draft HTA decision typically results in the company offering a risk sharing agreement in order to bring the new technology’s cost within the cost-effectiveness limit for the relevant country. In this case, the CMS is not an HTA agency. The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER), on the other hand, is an HTA agency, but it operates as a privately-funded organisation and its decisions are not binding. It also uses a broad cost-effectiveness range of $100,000-150,000 for each quality-adjusted life year (QALY), which has been criticised as being too high.

Regardless of the CMS’s lack of an HTA remit, the Aduhelm case highlights that the impact of a negative draft recommendation from the CMS is not dissimilar to the impact of a negative draft guidance from the UK’s NICE. It threatens to limit access to the treatment so severely as to be tantamount to lack of reimbursement for the vast majority of Medicare patients.

If the CMS’ negative proposed National Coverage Determination (NCD) for Aduhelm prompts Biogen to introduce even deeper Aduhelm price reductions than the 50% price cut announced last month, it may be a game-changer in US price control. While Aduhelm is an extreme case, if further price cuts are achieved, this could embolden the CMS to increasingly use the threat of non-reimbursement as a way to secure price cuts for other pharmaceuticals in the future.

Comment from