Image: Atomwise CEO and co-founder Abraham Heifets

Dry powder inhalers carry potential to decrease greenhouse emissions

As dry powder inhalers are breath controlled, no propellant is used, making their carbon footprint significantly lower than that of pMDIs, say GlobalData analysts.

Dr Judith M. Sills. Credit: Arriello

Dr Eric Caugant. Credit: Arriello

Asthma is a chronic respiratory condition that, according to GlobalData’s Epidemiology Database, affects approximately 14% of the UK population, and almost 88 million people in the seven major markets worldwide (US, UK, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Japan). Common symptoms include wheezing, shortness of breath, and limited airflow, which can vary in severity. Asthma is typically treated with a combination of a maintenance inhaler for everyday use and a rescue inhaler for symptom relief during asthma attacks.

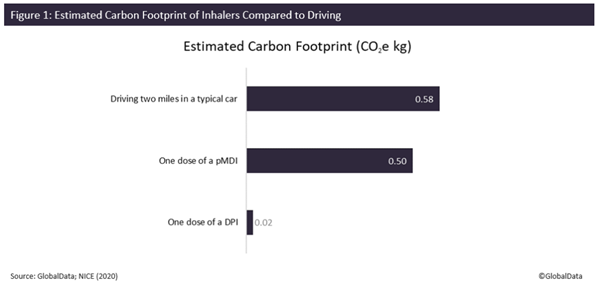

Commonly, inhalers will be pressurized metered dose inhalers (pMDIs), which use chemical propellants to administer the dose. However, these propellants have a carbon footprint. Before their ban, chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) were used as the propellant in most inhalers, which both contributed to the greenhouse effect and caused significant damage to the ozone layer. They have since been replaced with related hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), and while they do not deplete the ozone, are still powerful greenhouse gases (GHGs), and therefore have a carbon footprint. As the gas emitted is not CO2, this footprint is measured in CO2 equivalent kilograms (CO2e kg). According to the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Patient Decision Aid: Inhalers for Asthma guidance, one dose from a pMDI (0.5 CO2e kg) is comparable to driving almost two miles in a typical car (0.58 CO2e kg) (Figure 1). In addition, according to the UK’s National Health Service’s (NHS) Delivering a 'Net Zero' National Health Service report from 2020, the HFCs used as propellant in inhalers account for 3-4% of the healthcare related carbon footprint in the UK.

Dry powder inhalers (DPIs) provide an alternative to pMDIs. As they are breath controlled, no propellant is used, making their carbon footprint significantly lower than that of pMDIs. One dose from a DPI leads to only 4% of the emissions of a dose from a pMDI (Figure 1).

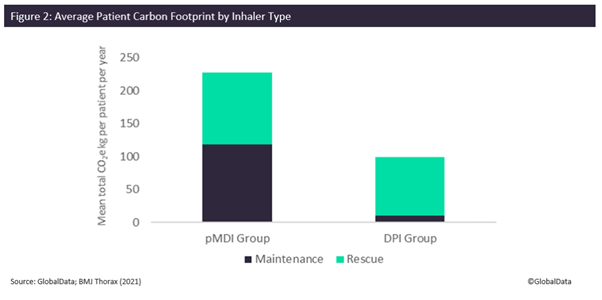

A study published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) monitored, over the course of a year, the effect of transitioning patients from their preexisting asthma treatment plan to DPIs. The average reduction in carbon footprint for patients in the DPI group was calculated and compared with the control group, as were the asthma outcomes. Throughout the study, the authors tallied the number of maintenance inhalers and rescue inhalers required by each patient. This was used to calculate the average carbon footprint for each patient. As salbutamol pMDI rescue inhalers were used by both groups, this did inflate the average carbon footprint of the DPI group, however the patients in the DPI group still more than halved their carbon footprint on average (227 CO2e kg per patient per year for usual treatment versus 99 CO2e kg per patient per year for the DPI group, a reduction of almost 60%) (Figure 2). Interestingly, there was also a reduction in number of rescue inhalers needed for those in the DPI group as compared to those who continued normal treatment. This could suggest that the use of DPIs leads to better patient outcomes as well as a reduction in carbon footprint.

The NHS has recently begun to encourage patients to transition from pMDIs to DPIs to reduce GHG emissions and combat the effects of climate change, which are only becoming more and more obvious. For maintenance inhalers, the cost of DPIs is comparable to pMDI equivalents, however, currently the cost of DPI rescue medication is still higher than that of pMDI rescue therapies. DPIs also are not a perfect solution for all patients. Due to the breath-controlled mechanism of action, they can be difficult to use for some demographics, including young children and elderly patients. It is likely that over the next few years, the market for DPIs will continue to grow as they replace pMDIs globally. This trend has already been seen across continental Europe, with pMDIs making up less than half of inhaler sales in some countries, and as little as 10% of sales in Sweden, as reported by NICE. The UK and US are lagging, with 70% and 88% of their respective markets comprising pMDIs, according to NICE and the Center for Disease Control (CDC) in the US. As such, there is a significant window for expansion here.

The transition of focus to DPIs could serve as an efficient way for pharma companies to meet environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) targets. According to GlobalData’s ESG Strategy Survey 2021, which involved 1,500 ESG leaders from 20 different industries, the environmental part of ESG was ranked the most important area of ESG by pharma leaders. Some pharma companies, such as AstraZeneca and GSK, have started to introduce low carbon alternatives for the propellant used in pMDIs. In September 2021, GSK announced that its lower GHG propellant was in preclinical trials, with the potential to reduce emissions from inhalers by 90%. In February 2022, AstraZeneca announced a partnership with Honeywell to develop an inhaler using Honeywell’s near-zero global warming potential (GWP) propellant. These could act as a viable solution for those who are not able to switch to a DPI, while still reducing overall carbon footprint. In addition, reducing the cost of DPI rescue therapies, thereby increasing their availability, will help improve the phase out of pMDI use in countries like the US and the UK.

ESG