Vaccines

Should UK children be vaccinated against chickenpox?

A safe and effective vaccine against chickenpox has been available since 1988 and has been part of routine childhood vaccinations in the US since 1995, but the same practice isn’t carried out in the UK, for surprisingly complex ethical reasons. Chloe Kent investigates the debate.

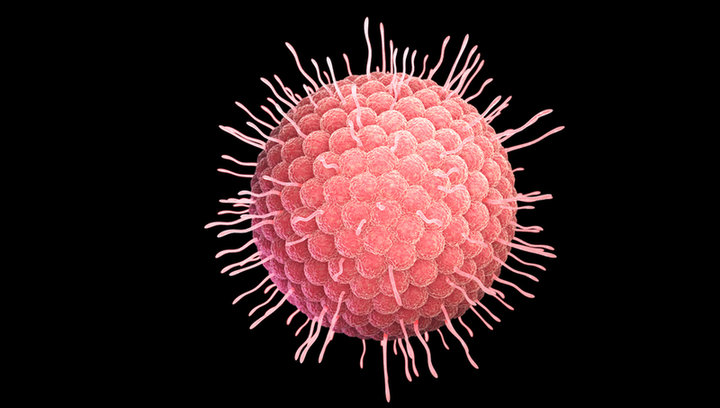

Typically seen as a mild childhood illness, chickenpox is an infection caused by the varicella-zoster virus. Although uncomfortable, and highly contagious, most people recover within a week or two.

The disease causes a blister-like rash that first appears on the face and torso and then spreads throughout the body. It also leads to flu-like symptoms such as fever, muscle aches and sometimes a loss of appetite or a feeling of nausea.

Occasionally, chickenpox produces more severe side effects, including bacterial skin infections, pneumonia and encephalitis. In the UK, hundreds of children are badly affected by the disease every year, and around 20 die as a result. In adults and older children, chickenpox is more severe, and the risk of complications increases with age.

As a result, chickenpox parties – social events where healthy young children are deliberately exposed to children infected with chickenpox, to try and ensure they catch the disease at a younger, less risky age – are not uncommon.

After a person recovers from chickenpox, the virus remains dormant inside their body in the nerves of the spinal cord and can reactivate later in life, causing a disease called shingles, aka herpes zoster. The reactivated varicella virus travels along the nerves and causes severe pain and a rash, usually affecting a single sensory nerve ganglion and the skin surface that the nerve supplies.

This often occurs on one side of the torso, but can also affect the face, eyes and genitals. The pain is caused by the involvement of the nerves, rather than the rash itself, and can last three to five weeks.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimate that one in three people infected with chickenpox as children will experience an episode of shingles in later life. Viral reactivation is more common in older people and people with weakened immune systems.

Moreover, the CDC estimates that around 10%-18% of people who get shingles go on to develop a complication called postherpetic neuralgia, where the shingles pain persists long after the rash has healed.

Fortunately, there are two effective varicella vaccines available – Varivax and Varilrix. Both vaccines contain a weakened strain of living varicella virus, which prompts the immune system to generate antibodies against natural infection. These weakened viruses may cause mild symptoms of illness post-vaccination but protect against outright chickenpox infection. The vaccines are 80 to 85% effective in preventing varicella disease and 95% effective in preventing severe disease.

While chickenpox vaccination has been part of routine childhood inoculation programmes in the US since 1995, the vaccine isn’t distributed by the NHS in the UK – for ethical reasons many deem controversial.

The risks of poor vaccine uptake

According to the UK NHS website, there are two key reasons why chickenpox vaccines aren’t routinely administered in the country. The first has a lot to do with the increasing severity of the disease as people age.

The NHS says: “If a childhood chickenpox vaccination programme were introduced, people would not catch chickenpox as children because the infection would no longer circulate in areas where the majority of children had been vaccinated.

It seems highly unlikely that UK parents would reject the chickenpox vaccine for their children while consenting to all the others

“This would leave unvaccinated children susceptible to contracting chickenpox as adults when they're more likely to develop a more severe infection or a secondary complication, or in pregnancy, when there's a risk of the infection harming the baby.”

If the chickenpox vaccine were introduced for young children in the UK but uptake was low, then reduced spread and consequential immunity during the early years would probably lead to a higher number of cases among older children and adults.

These people would then experience more severe illnesses with a higher risk of complications, increasing the burden of chickenpox on the healthcare system.

However, the majority of UK children already receive their childhood vaccines, with 2020’s uptake statistics showing that full vaccine coverage at five years in 2019-20 was 95.2%, an increase from 95% in 2018-19. As such, it seems highly unlikely that UK parents would reject the chickenpox vaccine for their children while consenting to all the others.

Critics of this reasoning also note that plenty of diseases are more severe in adults than children, like measles, mumps and rubella, yet these infections aren’t left to freely circulate among the population due to the risks of unvaccinated adults contracting more severe infections than they would have as children.

A living booster shot

The second reason that chickenpox isn’t part of the UK’s childhood vaccination programme is even more controversial. Some scientists think that being exposed to children with an active chickenpox infection will provide an immunity boost to adults who were infected with the disease, reducing the risk of a shingles reactivation.

While children with chickenpox will need to be kept away from adults who have never contracted or been vaccinated against the disease, adults who have had chickenpox are encouraged to spend time with infected children to minimise their shingles risk.

The NHS says: “Being exposed to chickenpox as an adult (for example, through contact with infected children) boosts your immunity to shingles.

The hypothesis of using children as living booster jabs may not have a strong basis in reality.

“If you vaccinate children against chickenpox, you lose this natural boosting, so immunity in adults will drop and more shingles cases will occur.”

However, the statistics in favour of this are shaky. Several studies and surveillance data show no consistent trends in shingles incidence in countries that have introduced routine childhood varicella vaccines, indicating that the hypothesis of using children as living booster jabs may not have a strong basis in reality.

But there are also more fundamental ethical objections to this practice. In a 2014 The Guardian editorial, University College London scientist Jenny Rohn argued that: “sick children should not be exploited as living vaccines for older people when there is a perfectly serviceable jab on the market – especially as the evidence that they really do stimulate a protective response against older people's shingles is not very robust.”

Varicella vaccines could eliminate shingles risk altogether

As well as protecting against chickenpox, varicella vaccines also seem to cut the risk of shingles occurring altogether. A 2019 US study found that approximately 38 in 100,000 children vaccinated against chickenpox developed shingles per year, compared to 170 per 100,000 unvaccinated children.

Paediatric shingles is already rare, and it’s not clear yet what these results could mean for adult shingles rates in the future.

The first generation to receive varicella vaccines in the US is currently in their early to mid-20s, and shingles reactivation becomes much more common after the age of 50, so researchers will need to follow a cohort of children who have been vaccinated against chickenpox and see what happens.

Approximately 38 in 100,000 children vaccinated against chickenpox developed shingles per year.

Nevertheless, it does appear that children who still get chickenpox after varicella vaccination are less likely to experience reactivation while they’re still young, and this immunity could feasibly extend into later adulthood and reduce adult shingles infections.

Pressure is now mounting on the UK Government to add varicella vaccination to the NHS programme. The country’s Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation was set to consider the matter last year, having ruled out a national rollout in 2010 on a cost-effectiveness basis, but the debate was curtailed by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Currently, paediatricians in the UK and worldwide are caught up in the messy business of deciding whether or not to immunise children against Covid-19. Many commentators hope that they will soon turn their attention to chickenpox too, bringing an end to the ‘pox party’ for good.

Preparing for the challenge ahead

To a large extent then, preparing for vaccine distribution will mean learning from what’s been achieved so far.

“I think some of it has to do with modelling – you can do a lot of simulation around production and distribution logistics,” says Boyle. “You can plan some ‘what if’ scenarios, at least identifying where the weaknesses are in the system and what kind of stressors would bring down parts of it. Then when you start to see the stressor, you already know it’ll cause a breakdown in the system and you already have a contingency plan.”

In practice, this might mean implementing a regional strategy with some redundancy in the supply chain, giving back-up if a certain country ends up in lockdown.

Delivering billions of doses of vaccine to the entire world efficiently will involve hugely complex logistical and programmatic obstacles.

“Everybody wants to operate at minimum inventory levels and maximum cost efficiency levels, but we’re asking now ‘where does lean become too lean?’” says Boyle. “The risk profile of that position has changed and people are going to be re-examining some of their goals. It’s about ensuring resilience of the supply chain and working out what level of risk you’re willing to take.”

With the first vaccines in sight, it is time for logistics providers, governments, airlines, and many more to begin their preparations in earnest. As the speakers emphasised at the IATA teleconference, this is an enormous undertaking that requires careful planning from every stakeholder.

“Delivering billions of doses of vaccine to the entire world efficiently will involve hugely complex logistical and programmatic obstacles all the way along the supply chain,” said Dr Seth Berkley, CEO of Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. “We look forward to working together with government, vaccine manufacturers and logistical partners to ensure an efficient global roll-out of a safe and affordable Covid-19 vaccine.”